Thomas Bernhard

Thomas Bernhard was an Austrian writer who ranks among the most distinguished German-speaking writers of the second half of the 20th century. Although internationally he’s most acclaimed because of his novels, he was also a prolific playwright. His characters are often at work on a lifetime and never-ending major project while they deal with themes such as suicide, madness and obsession, and, as Bernhard did, a love-hate relationship with Austria. His prose is tumultuous but sober at the same time, philosophic by turns, with a musical cadence and plenty of black humor. He started publishing in the year 1963 with the novel Frost. His last published work, appearing in the year 1986, was Extinction. Some of his best-known works include The Loser (about a student’s fictionalized relationship with the pianist Glenn Gould), Wittgenstein’s Nephew, and Woodcutters.

30 Books Written

Fiercely observed, often hilarious, and "reminiscent of Ibsen and Strindberg" (The New York Times Book Review), this exquisitely controversial novel was initially banned in its author's homeland. A searing portrayal of Vienna's bourgeoisie, it begins with the arrival of an unnamed writer at an 'artistic dinner' hosted by a composer and his society wife—a couple he once admired and has come to loathe. The guest of honor, a distinguished actor from the Burgtheater, is late. As the other guests wait impatiently, they are seen through the critical eye of the writer, who narrates a silent but frenzied tirade against these former friends, most of whom have been brought together by Joana, a woman they buried earlier that day. Reflections on Joana's life and suicide are mixed with these denunciations until the famous actor arrives, bringing an explosive end to the evening that even the writer could not have seen coming.

Thomas Bernhard was one of the most original writers of the twentieth century. His formal innovation ranks with Beckett and Kafka, his outrageously cantankerous voice recalls Dostoevsky, but his gift for lacerating, lyrical, provocative prose is incomparably his own.One of Bernhard's most acclaimed novels, The Loser centers on a fictional relationship between piano virtuoso Glenn Gould and two of his fellow students who feel compelled to renounce their musical ambitions in the face of Gould's incomparable genius. One commits suicide, while the other—the obsessive, witty, and self-mocking narrator—has retreated into obscurity. Written as a monologue in one remarkable unbroken paragraph, The Loser is a brilliant meditation on success, failure, genius, and fame.

It is 1967. In separate wings of a Viennese hospital, two men lie bedridden. The narrator, Thomas Bernhard, is stricken with a lung ailment; his friend Paul, nephew of the celebrated philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, is suffering from one of his periodic bouts of madness. As their once-casual friendship quickens, these two eccentric men begin to discover in each other a possible antidote to their feelings of hopelessness and mortality—a spiritual symmetry forged by their shared passion for music, a strange sense of humor, disgust for bourgeois Vienna, and fear in the face of death. Part memoir, part fiction, Wittgenstein’s Nephew is both a meditation on the artist’s struggle to maintain a solid foothold in a world gone incomprehensibly askew, and an eulogy to a real-life friendship.

Instead of the book he's meant to write, Rudolph, a Viennese musicologist, produces this tale of procrastination, failure, and despair, a dark and grotesquely funny story of small woes writ large and profound horrors detailed and rehearsed to the point of distraction."Certain books—few—assert literary importance instantly, profoundly. This new novel by the internationally praised but not widely known Austrian writer is one of those—a book of mysterious dark beauty . . . . [It] is overwhelming; one wants to read it again, immediately, to re-experience its intricate innovations, not to let go of this masterful work."—John Rechy, Los Angeles Times"Rudolph is not obstructed by some malfunctions in part of his being—his being itself is a knot. And as Bernhard's narrative proceeds, we begin to register the dimensions of his crisis, its self-consuming circularity . . . . Where rage of this intensity is directed outward, we often find the sociopath; where inward, the suicide. Where it breaks out laterally, onto the page, we sometimes find a most unsettling artistic vision."—Sven Birkerts, The New Republic

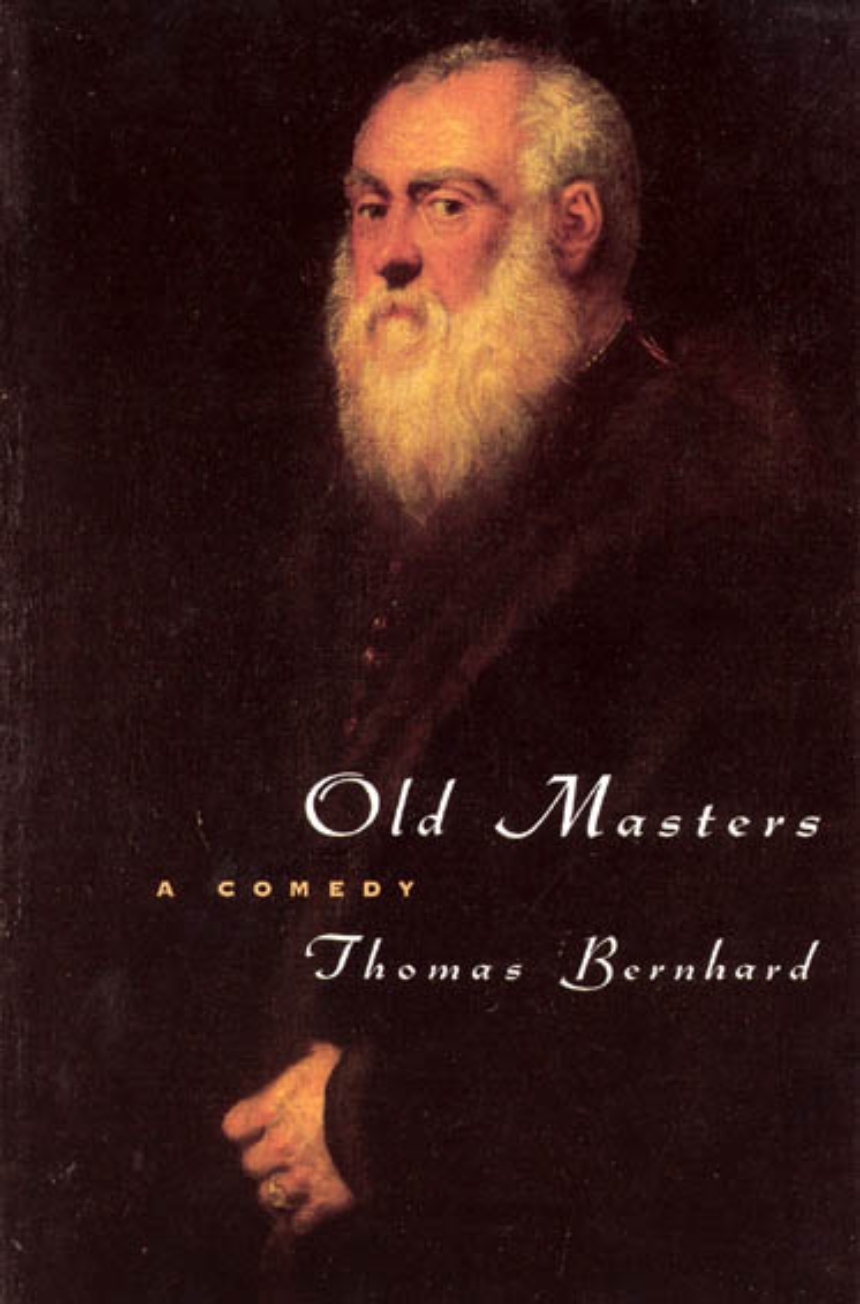

Old Masters (subtitled A Comedy) is a novel by the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard, which was first published in 1985. It tells of the life and opinions of Reger, a ‘musical philosopher’, through the voice of his acquaintance Atzbacher, a ‘private academic’.The book is set in Vienna on one day around the year of its publication, 1985. Reger is an 82-year-old music critic who writes pieces for The Times. For over thirty years he has sat on the same bench in front of Tintoretto’s White-bearded Man in the Bordone Room of the Kunsthistorisches Museum for four or five hours of the morning of every second day. He finds this environment the one in which he can do his best thinking. He is aided in this habit by the gallery attendant Irrsigler, who prevents other visitors from using the bench when Reger requires it.

Roithamer, a character based on Wittgenstein, has committed suicide having been driven to madness by his own frightening powers of pure thought. We witness the gradual breakdown of a genius ceaselessly compelled to correct and refine his perceptions until the only logical conclusion is the negation of his own soul.

Thomas Bernhard is one of the greatest twentieth-century writers in the German language. Extinction, his last novel, takes the form of the autobiographical testimony of Franz-Josef Murau. The intellectual black sheep of a powerful Austrian land-owning family, Murau lives in self-exile in Rome. Obsessed and angry with his identity as an Austrian, he resolves never to return to the family estate of Wolfsegg. But when news comes of his parents' deaths, he finds himself master of Wolfsegg and must decide its fate.Written in Bernhard's seamless style, Extinction is the ultimate proof of his extraordinary literary genius.

The playwright and novelist Thomas Bernhard was one of the most widely translated and admired writers of his generation, winner of the three most coveted literary prizes in Germany. Gargoyles, one of his earliest novels, is a singular, surreal study of the nature of humanity.One morning a doctor and his son set out on daily rounds through the grim mountainous Austrian countryside. They observe the colorful characters they encounter—from an innkeeper whose wife has been murdered to a crippled musical prodigy kept in a cage—coping with physical misery, madness, and the brutality of the austere landscape. The parade of human grotesques culminates in a hundred-page monologue by an eccentric, paranoid prince, a relentlessly flowing cascade of words that is classic Bernhard.

Visceral, raw, singular, and distinctive, Frost is the story of a friendship between a young man at the beginning of his medical career and a painter who is entering his final days.A writer of world stature, Thomas Bernhard combined a searing wit and an unwavering gaze into the human condition. Frost follows an unnamed young Austrian who accepts an unusual assignment. Rather than continue with his medical studies, he travels to a bleak mining town in the back of beyond, in order to clinically observe the aged painter, Strauch, who happens to be the brother of this young man’s surgical mentor. The catch is Strauch must not know the young man’s true occupation or the reason for his arrival. Posing as a promising law student with a love of Henry James, the young man befriends the mad artist and is caught up among an equally extraordinary cast of local characters, from his resentful landlady to the town’s mining engineers.This debut novel by Thomas Bernhard, which came out in German in 1963 and is now being published in English for the first time, marks the beginning of what was one of the twentieth century’s most powerful, provocative literary careers.

For twenty years, Konrad has imprisoned himself and his crippled wife in an abandoned lime works where he's conducted odd auditory experiments and prepared to write his masterwork, 'The Sense of Hearing.' As the story begins, he's just blown the head off his wife with the Mannlicher carbine she kept strapped to her wheelchair. The murder and the bizarre life that led to it are the subject of a mass of hearsay related by an unnamed life-insurance salesman in a narrative as mazy, byzantine, and mysterious as the lime works, Konrad's sanctuary and tomb.

Am 15. März 1938 verkündete Adolf Hitler unter den Jubelrufen der anwesenden Wiener auf dem Heldenplatz den »Anschluß« Österreichs an Deutschland. 50 Jahre später versammeln sich in einer Wohnung in der Nähe des Heldenplatzes die Familie Schuster und deren engste Freunde. Der Anlaß: das Begräbnis von Professor Josef Schuster. Für diesen philosophischen Kopf, von den Nazis verjagt, in den fünfziger Jahren auf Bitten des Wiener Bürgermeisters aus Oxford auf seinen Lehrstuhl zurückgekehrt, gab es keinen anderen Ausweg als den Selbstmord. Denn die Situation im gegenwärtigen Österreich sei »noch viel schlimmer als vor fünfzig Jahren«.

Die Ursachen waren zerstörend und verbrecherisch - sie hinterließen unauslöschliche Spuren. Das Internat: ein raffiniert gegen den Geist gebauter Kerker; die Stadt: eine Todeskrankheit, ein Friedhof der Phantasie und der Wünsche. Der Krieg: die Stollen, in denen Hunderte erstickt und umgekommen sind; der Großvater: der nur von Großem sprach, von Mozart, Rembrandt und Beethoven.All diese Belastungen hat Thomas Bernhard in diesem autobiographischen Rechenschaftsbericht literarisch verarbeitet.

The narrator, a scientist working on antibodies and suffering from emotional and mental illness, meets a Persian woman, the companion of a Swiss engineer, at an office in rural Austria. For the scientist, his endless talks with the strange Asian woman mean release from his condition, but for the Persian woman, as her own circumstances deteriorate, there is only one answer."Thomas Bernhard was one of the few major writers of the second half of this century."—Gabriel Josipovici, Independent"With his death, European letters lost one of its most perceptive, uncompromising voices since the war."— SpectatorWidely acclaimed as a novelist, playwright, and poet, Thomas Bernhard (1931-89) won many of the most prestigious literary prizes of Europe, including the Austrian State Prize, the Bremen and Brüchner prizes, and Le Prix SÃguier.

The Austrian playwright, novelist, and poet Thomas Bernhard (1931-89) is acknowledged as among the major writers of our times. At once pessimistic and exhilarating, Bernhard's work depicts the corruption of the modern world, the dynamics of totalitarianism, and the interplay of reality and appearance.In this stunning translation of The Voice Imitator, Bernhard gives us one of his most darkly comic works. A series of short parable-like anecdotes—some drawn from newspaper reports, some from conversation, some from hearsay—this satire is both subtle and acerbic. What initially appear to be quaint little stories inevitably indict the sterility and callousness of modern life, not just in urban centers but everywhere. Bernhard presents an ordinary world careening into absurdity and disaster. Politicians, professionals, tourists, civil servants—the usual victims of Bernhard's inspired misanthropy—succumb one after another to madness, mishap, or suicide. The shortest piece, titled "Mail," illustrates the anonymity and alienation that have become standard in contemporary society: "For years after our mother's death, the Post Office still delivered letters that were addressed to her. The Post Office had taken no notice of her death."In his disarming, sometimes hilarious style, Bernhard delivers a lethal punch with every anecdote. George Steiner has connected Bernhard to "the great constellation of Kafka, Musil, and Broch," and John Updike has compared him to Grass, Handke, and Weiss. The Voice Imitator reminds us that Thomas Bernhard remains the most caustic satirist of our age.

Eines Morgens beschließt der sechzehnjährige Gymnasiast auf dem Schulweg spontan, sich seinem bisherigen, verhaßten Leben zu entziehen und sich im Keller, einem Kolonialwarenladen, eine Lehrstelle zu verschaffen. Im Keller, am Rande der Salzburger Scherzhauserfeldsiedlung, dem heruntergekommenen, tristen Wohngetto der Besitzlosen, der Asozialen und Kriminellen, lernt Bernhard all die von der Gesellschaft Ausgestoßenen kennen, verstehen und ergreift Partei für diese verlorenen, verstörten Existenzen.

A gathering of brilliant and viciously funny recollections from one of the twentieth century’s most famous literary enfants terribles.Written in 1980 but published here for the first time, these texts tell the story of the various farces that developed around the literary prizes Thomas Bernhard received in his lifetime. Whether it was the Bremen Literature Prize, the Grillparzer Prize, or the Austrian State Prize, his participation in the acceptance ceremony—always less than gracious, it must be said—resulted in scandal (only at the awarding of the prize from Austria’s Federal Chamber of Commerce did Bernhard feel at he received that one, he said, in recognition of the great example he set for shopkeeping apprentices). And the remuneration connected with the prizes presented him with opportunities for adventure—of the new-house and luxury-car variety.Here is a portrait of the writer as a laconic, sardonic, and shaking his head with biting amusement at the world and at himself. A revelatory work of dazzling comedy, the pinnacle of Bernhardian art.

Auf regelmäßigen Spaziergängen berichtet Oehler, der früher mit Karrer ging, einem Dritten, warum Karrer verrückt geworden und nach Steinhof hinaufgekommen ist. Für Karrer war das Gehen Anlaß und Ausdruck seiner Denkbewegung. »Mit Karrer zu gehen, ist eine ununterbrochene Folge von Denkvorgängen gewesen«, Denkvorgänge, in den Karrer sich klarwerden wollte über die Beziehung des Denkens zu den Gegenständen, über das Verhältnis von Bewegung und Stillstand.

Die Schande einer unehelichen Geburt, die Alltagssorgen der Mutter und ihr ständiger Vorwurf: Du hast mein Leben zerstört! überschatten Thomas Bernhards Kindheitsjahre. Ein wahres Martyrium begann mit dem Eintritt in die Schule, in der sich der begabte Junge von Anfang an langweilte. Es waren Jahre fern der Idylle, wenn auch nicht ohne Augenblicke des Hochgefühls. Und es war die Zeit des Nationalsozialismus und des Krieges.

Born in 1931, the illegitimate child of an abandoned mother, Thomas Bernhard was brought up by an eccentric grandmother and adored grandfather. Tormented as a young student in a right-wing, catholic Austria, Bernhard ran away from home aged fifteen. At eighteen he contracted pneumonia. Placed in a hospital ward for the old and terminally ill, he observed with unflinching acuity protracted suffering and death. From the age of twenty-one, everything he wrote was shaped by the urgency of a dying man's testament – his witness, the quintessence of his life and knowledge – and where this account of his life ends, his art begins.

Nicht einmal achtzehnjährig wurde Thomas Bernhard im Jahre 1949 aus seinem musikalischen Studien durch eine schwere Krankheit herausgerissen. Er versinkt im stumpfen Weiß der Krankenhaussäle, dem geschulten Blick des Personals ausgeliefert, das ihn zielsicher unter die Sterbenden einordnet.Die letzte Station des gerade noch Lebenden ist das Badezimmer, aus dem nur die Toten wieder herauskommen. Umgeben von dieser Atmosphäre, die den Lebenswillen tötet, weiß er aber plötzlich, daß er nicht aufhören darf zu atmen, daß er leben will.

Mit der Einweisung in die Lungenheilstätte Grafenhof endet der dritte Teil von Thomas Bernhards Jugenderinnerungen, und ein neues Kapitel in der Leidensgeschichte des Achtzehnjährigen beginnt.Ein Schatten auf seiner Lunge verbannt ihn in die isolierte Welt des Sanatoriums, aus der es so leicht kein Entrinnen gibt. Ärzten, Pflegepersonal und Mitpatienten ausgeliefert, toben in ihm die widersprüchlichsten Gefühle. Mit nichts als Hoffnungslosigkeit konfrontiert, schwankt er immer wieder zwischen absoluter Anpassung und Auflehnung.

This collection of four stories by the writer George Steiner called “one of the masters of European fiction” is, as longtime fans of Thomas Bernhard would expect, bleakly comic and inspiringly rancorous. The subject of his stories vary: in one, Goethe summons Wittgenstein to discuss the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus; “Montaigne: A Story (in 22 Installments)” tells of a young man sealing himself in a tower to read; “Reunion,” meanwhile, satirizes that very impulse to escape; and the final story rounds out the collection by making Bernhard himself a victim, persecuted by his greatest enemy—his very homeland of Austria. Underpinning all these variously comic, tragic, and bitingly satirical excursions is Bernhard’s abiding interest in, and deep knowledge of, the philosophy of doubt.Bernhard’s work can seem off-putting on first acquaintance, as he suffers no fools and offers no hand to assist the unwary reader. But those who make the effort to engage with Bernhard on his own uncompromising terms will discover a writer with powerful comic gifts, penetrating insight into the failings and delusions of modern life, and an unstinting desire to tell the whole, unvarnished, unwelcome truth. Start here, readers; the rewards are great.

The cheap-eaters have been eating at the Vienna Public Kitchen for years, from Monday to Friday, and true to their name, always the cheapest meals. They become the focus of Koller’s scientific attention when he deviates one day from his usual path through the park, leading him to come upon the cheap-eaters and to realize that they must be the focal piece of his years-long, unwritten study of physiognomy. The narrator, a former school friend of Koller’s, tells of his relationship with Koller in a single unbroken paragraph that is both dizzying and absorbing. In Koller, the narrator observes a “gradually ever-growing and utterly exclusive interest in thought . . . . We can get close to such a person, but if we come into contact with him we will be repelled.” Written in Bernhard’s hyperbolic, darkly comic style, The Cheap-Eaters is a study of the limits of language and thought.

alternate-cover edition here»Das Wesen der Krankheit ist so dunkel als das Wesen des Lebens.« Dieses Zitat von Novalis steht als Motto über der 1964 geschriebenen Erzählung Thomas Bernhards. Beschrieben wird die letzte Phase im Auflösungsprozeß einer Familie, Ursache und Wirkung eines allmählichen Niedergangs, der auf ebenso geheimnisvolle wie bestimmte Weise mit der Landschaft im Zusammenhang steht. Die Tragödie erfüllt sich an zwei letzten Überlebenden, einem Brüderpaar. Das in Zuneigung und Abneigung ambivalente, durch Krankheit sich mehr und mehr verschärfende Verhältnis der Brüder zueinander bildet ein Spannungsfeld, in dem Leben und Tod, Geist und Natur, die Finsternis und die Hellhörigkeit des Schmerzes einander begegnen, sich verbinden, sich spiegeln.

Ein junger Mann reist, um eine Erbschaftsangelegenheit zu regeln, in seinen Heimatort. Konfrontiert mit der Vergangenheit, endeckt er, dass er auf die Fragen, die sie aufwirft, keine Antwort weiß, dass er sie nicht ertragen kann.

“His manner of speaking, like that of all the subordinated, excluded, was awkward, like a body full of wounds, into which at any time anyone can strew salt, yet so insistent, that it is painful to listen to him,” from The Carpenter The Austrian playwright, novelist, and poet Thomas Bernhard (1931–89) is acknowledged as among the major writers of our time. The seven stories in this collection capture Bernhard’s distinct darkly comic voice and vision—often compared to Kafka and Musil—commenting on a corrupted world. First published in German in 1967, these stories were written at the same time as Bernhard’s early novels Frost , Gargoyles , and The Lime Works , and they display the same obsessions, restlessness, and disarming mastery of language. Martin Chalmer’s outstanding translation, which renders the work in English for the first time, captures the essential personality of the work. The narrators of these stories lack the strength to do anything but listen and then write, the reader in turn becoming a captive listener, deciphering the traps laid by memory—and the mere words, the neverending words with which we try to pin it down. Words that are always close to driving the narrator crazy, but yet, as Bernhard writes “not completely crazy.” “Bernhard's glorious talent for bleak existential monologues is second only to Beckett's, and seems to have sprung up fully mature in his mesmerizing debut.”—From Publishers Weekly, on Frost “The feeling grows that Thomas Bernhard is the most original, concentrated novelist writing in German. His connections . . . with the great constellation of Kafka, Musil, and Broch become ever clearer.” —George Steiner, Times Literary Supplement , on GargoylesCONTENTSTwo tutorsThe capIs it a comedy? Is it a tragedy?JaureggAttaché at the French EmbassyThe crime of an Innsbruck shopkeeper's sonThe Carpenter

Vier Männer gehen zu einem Gastwirt, so wie seit Jahren, zum Watten, zum Kartenspiel. Aber das Kartenspiel findet an diesem Abend nicht statt, der Gastwirt wartet vergebens auf seine Mitspieler. Warum es an diesem Abend nicht zum Watten kommt, das behandelt die Erzählung.

Claus Peymann kauft sich eine Hose und geht mit mir essen. Drei Dramolette

by Thomas Bernhard

Rating: 4.0 ⭐

Trzy sztuki teatralne Thomasa Bernharda sa poswiecone wybitnemu niemieckiemu rezyserowi Clausowi Peymannowi, pelniacemu w latach 1986 - 1999 funkcje dyrektora slynnego Burgtheater, w którym zaprezentowal on wiele znakomitych inscenizacji swiatowych arcydziel teatralnych, a takze wyrezyserowal m. in. owiany aura skandalu Heldenplatz. Bernhard, niezrównany mistrz groteskowego przerysowania, jak zwykle poddaje nieslychanie ostrej krytyce stosunki panujace w Austrii, wysmiewa i wyszydza instytucje kulturalne. W ironiczny sposób charakteryzuje tez siebie, Peymanna oraz dramaturga Burgtheater - Beila.

Written as one sentence, On The Mountain is a monologue delivered by a court reporter who encounters a variety of characters during the course of his day. It was Bernhard's first prose work which he completed in 1959.

In letteratura gli avvenimenti sono sempre più rari. Come tale fu salutata la pubblicazione di quest'opera che, insieme a Perturbamento, portò per la prima volta all'attenzione dei lettori italiani la prosa di Thomas Bernhard, uno scrittore che, come scrive il germanista Giorgio Cusatelli, "registra, simile a un burocrate e senza un'ombra di misticismo, i progressi quotidiani del male."Tre racconti - Kulterer, L'Italiano e Al limite boschivo - che "fotografano l'unica follia senza scampo, quella della razionalit". Dall'alienazione di Al limite boschivo in cui si arriva addirittura a proclamare "la reciproca vacuità della vita e della morte."La meditazione di Bernhard, però, per quanto estrema, non si accende mai in un'invettiva o in un'accusa esplicita nei confronti di un Dio latitante, ma si mantiene sempre sul tono di una pura cronaca, dove i fatti sono sempre opera altrui e perfino chi li racconta non esce mai allo scoperto.