Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz grew up in rural Oklahoma in a tenant farming family. She has been active in the international Indigenous movement for more than 4 decades and is known for her lifelong commitment to national and international social justice issues. Dunbar-Ortiz is the winner of the 2017 Lannan Cultural Freedom Prize, and is the author or editor of many books, including An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, a recipient of the 2015 American Book Award. She lives in San Francisco. Connect with her at reddirtsite.com or on Twitter @rdunbaro.

16 Books Written

“All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Rating: 4.1 ⭐

• 2 recommendations ❤️

Unpacks the twenty-one most common myths and misconceptions about Native AmericansIn this enlightening book, scholars and activists Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker tackle a wide range of myths about Native American culture and history that have misinformed generations. Tracing how these ideas evolved, and drawing from history, the authors disrupt long-held and enduring myths such as:"Columbus Discovered America""Thanksgiving Proves the Indians Welcomed Pilgrims""Indians Were Savage and Warlike""Europeans Brought Civilization to Backward Indians""The United States Did Not Have a Policy of Genocide""Sports Mascots Honor Native Americans""Most Indians Are on Government Welfare""Indian Casinos Make Them All Rich""Indians Are Naturally Predisposed to Alcohol"Each chapter deftly shows how these myths are rooted in the fears and prejudice of European settlers and in the larger political agendas of a settler state aimed at acquiring Indigenous land and tied to narratives of erasure and disappearance. Accessibly written and revelatory, "All the Real Indians Died Off" challenges readers to rethink what they have been taught about Native Americans and history.

The first history of the United States told from the perspective of indigenous peoples Today in the United States, there are more than five hundred federally recognized Indigenous nations comprising nearly three million people, descendants of the fifteen million Native people who once inhabited this land. The centuries-long genocidal program of the US settler-colonial regimen has largely been omitted from history. Now, for the first time, acclaimed historian and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz offers a history of the United States told from the perspective of Indigenous peoples and reveals how Native Americans, for centuries, actively resisted expansion of the US empire.With growing support for movements such as the campaign to abolish Columbus Day and replace it with Indigenous Peoples’ Day and the Dakota Access Pipeline protest led by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States is an essential resource providing historical threads that are crucial for understanding the present. In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Dunbar-Ortiz adroitly challenges the founding myth of the United States and shows how policy against the Indigenous peoples was colonialist and designed to seize the territories of the original inhabitants, displacing or eliminating them. And as Dunbar-Ortiz reveals, this policy was praised in popular culture, through writers like James Fenimore Cooper and Walt Whitman, and in the highest offices of government and the military. Shockingly, as the genocidal policy reached its zenith under President Andrew Jackson, its ruthlessness was best articulated by US Army general Thomas S. Jesup, who, in 1836, wrote of the Seminoles: “The country can be rid of them only by exterminating them.” Spanning more than four hundred years, this classic bottom-up peoples’ history radically reframes US history and explodes the silences that have haunted our national narrative.An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States is a 2015 PEN Oakland-Josephine Miles Award for Excellence in Literature.

Not "A Nation of Immigrants": Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Rating: 4.3 ⭐

Debunks the pervasive and self-congratulatory myth that our country is proudly founded by and for immigrants, and urges readers to embrace a more complex and honest history of the United StatesWhether in political debates or discussions about immigration around the kitchen table, many Americans, regardless of party affiliation, will say proudly that we are a nation of immigrants. In this bold new book, historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz asserts this ideology is harmful and dishonest because it serves to mask and diminish the US’s history of settler colonialism, genocide, white supremacy, slavery, and structural inequality, all of which we still grapple with today.She explains that the idea that we are living in a land of opportunity - founded and built by immigrants - was a convenient response by the ruling class and its brain trust to the 1960s demands for decolonialization, justice, reparations, and social equality. Moreover, Dunbar-Ortiz charges that this feel good - but inaccurate - story promotes a benign narrative of progress, obscuring that the country was founded in violence as a settler state, and imperialist since its inception.While some of us are immigrants or descendants of immigrants, others are descendants of white settlers who arrived as colonizers to displace those who were here since time immemorial, and still others are descendants of those who were kidnapped and forced here against their will. This paradigm shifting new book from the highly acclaimed author of An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States charges that we need to stop believing and perpetuating this simplistic and a historical idea and embrace the real (and often horrific) history of the United States.

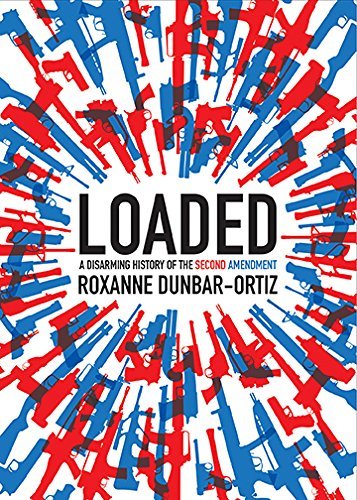

The New Republic Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment , is a deeply researched—and deeply disturbing—history of guns and gun laws in the United States, from the original colonization of the country to the present. As historian and educator Dunbar-Ortiz explains, in order to understand the current obstacles to gun control, we must understand the history of U.S. guns, from their role in the "settling of America" and the early formation of the new nation, and continuing up to the present.

In 1968, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz became a founding member of the early women's liberation movement. Along with a small group of dedicated women, she produced the seminal journal series, No More Fun and Games. Her group, Cell 16 occupied the radical fringe of the growing movement, considered too outspoken and too outrageous by mainstream advocates for women's rights.Dunbar-Ortiz was also a dedicated anti-war activist and organizer throughout the 1960s and 1970s. During the war years she was a fiery, indefatigable public speaker on issues of patriarchy, capitalism, imperialism, and racism. She worked in Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade, and formed associations with other revolutionaries across the spectrum of radical and underground politics, including the SDS, the Weather Underground, the Revolutionary Union, and the African National Congress. But unlike the majority of those in the New Left—young white men from solidly middle-class suburban families—Dunbar-Ortiz grew up poor, female, and part-Indian in rural Oklahoma, and she often found herself at odds not only with the ruling class but also with the Left and with the women's movement.Dunbar-Ortiz's odyssey from dust-bowl poverty to the urban radical fringes of the New Left gives a working-class, feminist perspective on a time and a movement which forever changed American society."Roxanne Dunbar gives the lie to the myth that all New Left activists of the 60s and 70s were spoiled children of the suburban middle classes. Read this book to find out what are the roots of radicalism—anti-racist, pro-worker, feminist—for a child of working-class Okie background."—Mark Rudd, SDS, Columbia University strike leaderRoxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is a historian and professor in the Department of Ethnic Studies at California State University, Hayward. She is the author of Red Dirt: Growing up Okie, The Great Sioux Nation, and Roots of Resistance, among other books.

A classic in contemporary Oklahoma literature, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s Red Dirt unearths the joys and ordeals of growing up poor during the 1940s and 1950s. In this exquisite rendering of her childhood in rural Oklahoma, from the Dust Bowl days to the end of the Eisenhower era, the author bears witness to a family and community that still cling to the dream of America as a republic of landowners.

An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States for Young People

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Rating: 4.3 ⭐

With Blood on the A Memoir of the Contra War , Dunbar-Ortiz presents the third volume in her critically acclaimed memoir. In this long-awaited book, she vividly recounts on-the-ground memories of the contra war in Nicaragua, chronicling the US-sponsored terror inflicted on the people of Nicaragua following their 1981 election of the socialist Sandinistas, ousting Reagan darling and vicious dictator Somoza. The war’s opening salvo was the bombing of a Nicaraguan plane in Mexico City by US-backed contras, the plane Dunbar-Ortiz would have been on were it not for a delay. This disarming closeness to the fraught history of the US/Nicaraguan relationship shapes Dunbar-Ortiz’s narrative, bringing uncomfortably present the decade-long dirty war that the Reagan administration pursued in Nicaragua against civilian and soldier alike. As with her first two memoirs, in Blood on the Border , Dunbar-Ortiz seamlessly connects the dots not only between the personal and the political, but between recent history and our present moment. Unlike the many commentators who view the September 11, 2001, attacks as the start of the so-called “war on terror,” Dunbar-Ortiz offers firsthand testimony on battles waged much earlier. While her rich political analysis of this history bears the mark of a trained historian, she also writes from her perspective as an intrepid activist who spent months at a time throughout the 1980s in the war-torn country, especially in the remote Mosquitia region, where the indigenous Miskitu people were viciously assailed and nearly wiped out by CIA-trained contra mercenaries. She makes painfully clear the connections between what many US Americans only remember vaguely as the Iran-Contra “affair” and current US aggression in the Americas, the Middle East, and around the world. Clearly, this will be a book valuable not only for students of Latin American history, but also for anyone who is interested in better understanding the violent turmoil of our world today.

An updated edition of a seminal work on the history of land ownership in the Southwest In New Mexico―once a Spanish colony, then part of Mexico―Pueblo Indians and descendants of Spanish- and Mexican-era settlers still think of themselves as distinct peoples, each with a dynamic history. At the core of these persistent cultural identities is each group’s historical relationship to the others and to the land, a connection that changed dramatically when the United States wrested control of the region from Mexico in 1848. In Roots of Resistance ―now offered in an updated paperback edition―Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz provides a history of land ownership in northern New Mexico from 1680 to the present. She shows how indigenous and Mexican farming communities adapted and preserved their fundamental democratic social and economic institutions, despite losing control of their land to capitalist entrepreneurs and becoming part of a low-wage labor force. In a new final chapter, Dunbar-Ortiz applies the lessons of this history to recent conflicts in New Mexico over ownership and use of land and control of minerals, timber, and water.

The Great Sioux nation: Sitting in judgement on America : based on and containing testimony heard at the "Sioux treaty hearing" held December, 1974, in Federal District Court, Lincoln, Nebraska

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Rating: 4.4 ⭐

“If the moral issues raised by the Sioux people in the federal courtroom that cold month of December 1974 spark a recognition among the readers of a common destiny of humanity over and above the rules and regulations, the codes and statutes, and the power of the establishment to enforce its will, then the sacrifice of the Sioux people will not have been in vain.”—Vine Deloria Jr.The Great Sioux Sitting in Judgment on America is the story of the Sioux Nation’s fight to regain its land and sovereignty, highlighting the events of 1973–74, including the protest at Wounded Knee. It features pieces by some of the most prominent scholars and Indian activists of the twentieth century, including Vine Deloria Jr., Simon Ortiz, Dennis Banks, Father Peter J. Powell, Russell Means, Raymond DeMallie, and Henry Crow Dog. It also features primary documents and firsthand accounts of the activists’ work and of the trial.New to this Bison Books edition is a foreword by Philip J. Deloria and an introduction by Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz.

Settler Colonialism examines the genesis in the USA of the first full-fledged settler state in the world, which went beyond its predecessors in 1492 Iberia and British-colonized Ireland with an economy based on land sales and enslaved African labor, an implementation of the fiscal-military state. Both the liberal and the rightwing versions of the national narrative misrepresent the process of European colonization of North America. Both narratives serve the critical function of preserving the “official story” of a mostly benign and benevolent USA as an anticolonial movement that overthrew British colonialism. The pre-US independence settlers were colonial settlers just as they were in Africa and India or like the Spanish in Central and South America. The nation of immigrants myth erases the fact that the United States was founded as a settler state from its inception and spent the next hundred years at war against the Native Nations in conquering the continent. Buried beneath the tons of propaganda—from the landing of the English “pilgrims” (Protestant Christian evangelicals) to James Fenimore Cooper’s phenomenally popular The Last of the Mohicans claiming settlers’ “natural rights” not only to the Indigenous peoples’ territories but also to the territories claimed by other European powers—is the fact that the founding of the United States created a division of the Anglo empire, with the US becoming a parallel empire to Great Britain, ultimately overcoming it. From day one, as was specified in the Northwest Ordinance, which preceded the US Constitution, the new “republic for empire,” as Thomas Jefferson called the new United States, envisioned the future shape of what is now the forty-eight states of the continental US. The founders drew up rough maps, specifying the first territory to conquer as the “Northwest Territory.” That territory was the Ohio Valley and the Great Lakes region, which was already populated with Indigenous villages and farming communities thousands of years old. Even before independence, mostly Scots Irish settlers had seized Indigenous farmlands and hunting grounds in the Appalachians and are revered historically as first settlers and rebels, who in the mid-twentieth century began claiming indigeneity. Self-indigenizing by various groups of settlers is a recurrent theme in story of settler colonialism, white supremacy, and the history of erasure and exclusion about which I have written elsewhere.

The Miskito Indians of Nicaragua

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Economic Development in American Indian Reservations

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

American Indian Energy Resources and Development

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Contre-histoire des Etats-Unis

by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Ce livre répond à une question simple : pourquoi les Indiens d'Amérique ont-ils été décimés? N'était-il pas pensable de créer une civilisation créole prospère qui permette aux populations amérindienne, africaine, européenne, asiatique et océanienne de partager l'espace et les ressources naturelles des États-Unis? Le génocide des Amérindiens était-il inéluctable?La thèse dominante aux États-Unis est qu'ils ont souvent été tués par les virus apportés par les Européens avant même d'entrer en contact avec les Européens eux-mêmes : la variole voyageait plus vite que les soldats espagnols et anglais. Les survivants auraient soit disparu au cours des guerres de la frontière, soit été intégrés, eux aussi, à la nouvelle société d'immigrés.Contre cette vision irénique d'une histoire impersonnelle, où les virus et l'acier tiennent une place prépondérante et où les intentions humaines sont secondaires, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz montre que les États-Unis sont une scène de crime. Il y a eu génocide parce qu'il y a eu intention d'exterminer : les Amérindiens ont été méthodiquement éliminés, d'abord physiquement, puis économiquement, et enfin symboliquement.