Ernst Jünger

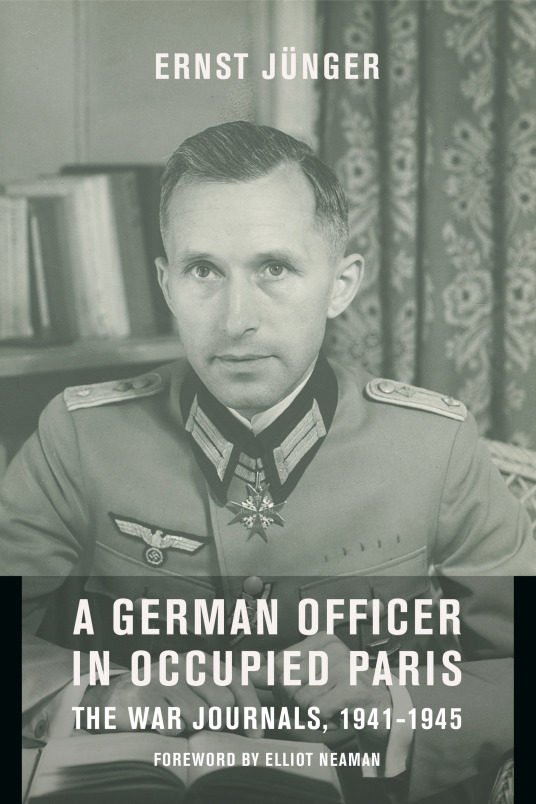

Ernst Jünger was a decorated German soldier and author who became famous for his World War I memoir Storm of Steel. The son of a successful businessman and chemist, Jünger rebelled against an affluent upbringing and sought adventure in the Wandervogel, before running away to briefly serve in the French Foreign Legion, an illegal act. Because he escaped prosecution in Germany due to his father's efforts, Junger was able to enlist on the outbreak of war. A fearless leader who admired bravery above all else, he enthusiastically participated in actions in which his units were sometimes virtually annihilated. During an ill-fated German offensive in 1918 Junger's WW1 career ended with the last and most serious of his many woundings, and he was awarded the Pour le Mérite, a rare decoration for one of his rank. Junger served in World War II as captain in the German Army. Assigned to an administrative position in Paris, he socialized with prominent artists of the day such as Picasso and Jean Cocteau. His early time in France is described in his diary Gärten und Straßen (1942, Gardens and Streets). He was also in charge of executing younger German soldiers who had deserted. In his book Un Allemand à Paris , the writer Gerhard Heller states that he had been interested in learning how a person reacts to death under such circumstances and had a morbid fascination for the subject. Jünger appears on the fringes of the Stauffenberg bomb plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler (July 20, 1944). He was clearly an inspiration to anti-Nazi conservatives in the German Army, and while in Paris he was close to the old, mostly Prussian, officers who carried out the assassination attempt against Hitler. He was only peripherally involved in the events however, and in the aftermath suffered only dismissal from the army in the summer of 1944, rather than execution. In the aftermath of WW2 he was treated with some suspicion as a closet Nazi. By the latter stages of the Cold War his unorthodox writings about the impact of materialism in modern society were widely seen as conservative rather than radical nationalist, and his philosophical works came to be highly regarded in mainstream German circles. Junger ended his extremely long life as a honoured establishment figure, although critics continued to charge him with the glorification of war as a transcending experience.

30 Books Written

The memoir widely viewed as the best account ever written of fighting in WW1A memoir of astonishing power, savagery, and ashen lyricism, Storm of Steel illuminates not only the horrors but also the fascination of total war, seen through the eyes of an ordinary German soldier. Young, tough, patriotic, but also disturbingly self-aware, Jünger exulted in the Great War, which he saw not just as a great national conflict but—more importantly—as a unique personal struggle. Leading raiding parties, defending trenches against murderous British incursions, simply enduring as shells tore his comrades apart, Jünger kept testing himself, braced for the death that will mark his failure. Published shortly after the war’s end, Storm of Steel was a worldwide bestseller and can now be rediscovered through Michael Hofmann’s brilliant new translation.For more than sixty-five years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,500 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

The peaceful and traditional people, located on the shores of a large bay, are surrounded by the rough pastoral folk in the surrounding hills, who feel increasing pressure from the unscrupulous and lowly followers of the dreaded head forester. The narrator and protagonist lives on the marble cliffs as a botanist with his brother Otho, his son Erio from a past relationship and Erio's grandmother Lampusa. The idyllic life is threatened by the erosion of values and traditions, losing its inner power. The head forester uses this opportunity to establish a new order based on dictatorial rule, large numbers of mindless followers and the use of violence, torture and murder.

In The Glass Bees the celebrated German writer Ernst Jünger presents a disconcerting vision of the future. Zapparoni, a brilliant businessman, has turned his advanced understanding of technology and his strategic command of the information and entertainment industries into a discrete form of global domination. But Zapparoni is worried that the scientists he depends on might sell his secrets. He needs a chief of security, and Richard, a veteran and war hero, is ready for the job. However, when he arrives at the beautiful country compound that is Zapparoni's headquarters, he finds himself subjected to an unexpected ordeal. Soon he is led to question his past, his character, and even his senses....

Ernst Jünger's The Forest Passage explores the possibility of resistance: how the independent thinker can withstand and oppose the power of the omnipresent state. No matter how extensive the technologies of surveillance become, the forest can shelter the rebel, and the rebel can strike back against tyranny. Jünger's manifesto is a defense of freedom against the pressure to conform to political manipulation and artificial consensus. A response to the European experience under Nazism, Fascism, and Communism, The Forest Passage has lessons equally relevant for today, wherever an imposed uniformity threatens to stifle liberty."In a strikingly poetic political statement written soon after the Second World War, Ernst Jünger rejects the two reigning ideologies, democracy and communism, in favor of an individualistic stance anticipating what we now call libertarianism. The ideal that Jünger projects for us is a metaphorical 'passage through the forest' in which we remain constantly put to the test, with the result that we emerge self-sufficient, rebellious, heroic."--Herbert Lindenberger, Stanford University"The Forest Rebel says no to power, outwardly unobtrusive but inwardly rebellious and martial, spiritually, politically, and intellectually, an anarch as opposed to an anarchist. Many of the ideas here reflect Germany's geopolitical situation in the Cold War, powerless against the occupiers of East and West. But the treatise transcends the context in which it was born and manifests Jünger's sharp analysis of trends and problems that are as relevant today as ever. Particularly in the age of the mass plebiscite called the internet and as the marriage of the state and technology has given government unprecedented power over its citizens, a book about how to resist modern forms of tyranny is timely and much needed."--Elliot Neaman, University of San Francisco"In the Anglophone world the intellectual and writer Ernst Jünger has been overshadowed by the image of the fierce World War I warrior and the radical right-wing ideologue of the 1920s. The result has been an uneven and one-sided public reception that has severely underestimated the significance and complexity of Jünger's literary oeuvre. Especially his late work has barely been noticed. A critical revision of old approaches is definitely overdue. Therefore the publication of The Forest Passage is a truly important step in the right direction."--Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University"This fascinating work seeks out a place of inner subjective freedom where the besieged citizen of the modern world may withhold consent and refuse participation in the hellish tyranny of administrative totalitarianism. Jünger invites his reader to become a passenger in this forest of thoughtful reflection beyond the reach of political coercion and conformism."--Robert Harrison, Stanford University

Written and published in 1934, a year after Hitler's rise to power in Germany, Ernst Jünger's On Pain is an astonishing essay that announces the rise of a new metaphysics of pain in a totalitarian age. One of the most controversial authors of twentieth-century Germany, Jünger rejects the liberal values of liberty, security, ease, and comfort, and seeks instead the measure of man in the capacity to withstand pain and sacrifice. Jünger heralds the rise of a breed of men who--equipped with an unmatched ability to treat themselves and others in a cold and detached way--become one with new, terrorizing machines of death and destruction in human-guided torpedoes and manned airborne missiles, and whose "peculiarly cruel way of seeing," resembling the insensitive lens of a camera, anticipates the horrors of World War II. With a preface by Russell A. Berman, and an introduction by translator David C. Durst, this remarkable essay not only provides valuable insights into the cult of courage and death in Nazi Germany, but also throws light on the ideology of terrorism today.<

Originally published in Germany in 1977, when Junger was eighty-two years old, Eumeswil is the great novel of Junger's creative maturity, a masterpiece by a central figure in modern German literature. Eumeswil is a utopian state ruled by the Condor, a general who has installed himself as a dictator and who dominates the capital from a guarded citadel atop a hill - the Casbah. A refined manipulator of power, the Condor despises the democrats who conspire against him. Venator, the narrator of the novel, is a historian whose discreet and efficient services as the Condor's night steward earn him full access to the forbidden zone, at the very heart of power. Every evening, while attending to the Condor and his guests at the Casbah's night bar, Venator keeps a secret journal in which he records the conversations he overhears, delineating the diverse personalities in the Condor's entourage while sketching out an analysis of the different aspects of the psychology of power. Venator's days are spent building a hidden refuge in the mountains, a hermetic retreat where he hopes one day to realize his dreams of utter self-sufficiency. In the meantime, however, he continues to pursue his career as a historian, using the magnificent tool that has been placed at his disposal - the "luminar", a holographic instrument that can summon up any figure or event in human history. Venator, in a word, embodies Junger's ideal of the "anarch" - a heroic figure whose radical skepticism and individualism are not to be confused with mere anarchism. Around the opposite figures of the dictator and the anarch, Junger weaves a hallucinatory and poetic rumination on the nature of history and on the mainsprings of political power. At once tale, essay and philosophical poem, Eumeswil offers a desolate and lucid assessment of totalitarianism by an author who witnessed its horrors firsthand.

In questo saggio breve scritto immediatamente dopo la fine delle ostilità e la sconfitta dell'Impero tedesco - l'unico lavoro rimasto inedito in Italia dello scrittore tedesco - Jünger analizza con una prosa ispirata e toccante l'esperienza e le conseguenze materiali e spirituali del disastro della Prima guerra mondiale, tema che segnerà in modo indelebile la produzione letteraria e filosofica dello scrittore e filosofo tedesco. Ne "La battaglia come esperienza interiore" Jünger riporta l'esperienza terribile della guerra di trincea, luogo dove rivivono gli istinti e le stesse pulsioni ferine che hanno dominato i nostri avi - la stessa volontà di sopraffare e di conquistare. Il vero uomo e il vero soldato è però capace di comprenderle e di dominarle, arricchendo l'esperienza con il senso dell'onore e del rispetto per il nemico. L'artista, lo scrittore, il genio di Jünger è anche capace, oltre a tutto questo, di trasformare tali sensazioni ed esperienze in pura epica, permettendoci di comprendere l'orrore nelle sue molteplici sfaccettature.

Die Erzählung "Sturm" erschien im April 1923 in Fortsetzungen in der Tageszeitungen "Hannoverscher Kurier". Sie galt als verschollen, war ihrem Autor selbst aus der Erinnerung entschwunden und wurde 1960 wiederaufgefunden...Wie ein junger Mensch des zivilisierten Europa mit der furchtbaren Erscheinung des modernen Krieges und seiner Schlachtfelder fertig zu werden sucht, das hat Ernst Jünger in seinen frühen Schriften als einer der ersten im deutschen Sprachbereich dargestellt. Kennzeichnend für "Sturm" ist nun sowohl die Form der Erzählung, die einen Versuch in dieser literarischen Kategorie erprobt, als auch der expressionistische Charakter ihres Stils. Wie stark die Figur des Leutnant Sturm autobiographisch zu verstehen ist, zeigt sich darin, daẞ der Autor 927 Vorabdrucke aus seinem "Abenteuerlichen Herzen" unter dem Pseudonym Hans Sturm erschienen lieẞ. Es gibt keine bessere Porträtskizze des jungen Autors, als er sie im letzten Abschnitt des zweiten Kapitels unserer Erzählung von seiner Titelfigur gegeben hat.

Ernst Jünger was one of twentieth-century Germany’s most important—and most controversial—writers. Decorated for bravery in World War I and the author of the acclaimed memoir from the western front, Storm of Steel, he frankly depicted the war’s horrors even as he extolled its glories. As a Wehrmacht captain during the Second World War, Jünger faithfully kept a journal in occupied Paris and continued to write on the eastern front and in Germany until its defeat—writings that are of major historical and literary significance.Jünger’s Paris journals document his Francophile excitement, romantic affairs, and fascination with botany and entomology, alongside mystical and religious ruminations and trenchant observations on the occupation and the politics of collaboration. Working as a mail censor, he led the privileged life of an officer, encountering artists such as Céline, Cocteau, Braque, and Picasso. His notes from the Caucasus depict chaos and misery after the defeat at Stalingrad, as well as candid comments about the atrocities on the eastern front. Returning to Paris, Jünger observed resistance and was peripherally involved in the 1944 conspiracy to assassinate Hitler. After fleeing France, he reunited with his family as Germany’s capitulation approached. Both participant and commentator, close to the horrors of history but often hovering above them, Jünger turned his life and experiences into a work of art. These wartime journals appear here in English for the first time, giving us fresh insight into the quandaries of the twentieth century from the keen pen of a paradoxical observer.Ernst Jünger (1895–1998) was a major figure in twentieth-century German literature and intellectual life. He was a young leader of right-wing nationalism in the Weimar Republic, but although the Nazis tried to court him, Jünger steadfastly kept his distance from their politics. Among his works is On the Marble Cliffs, a rare anti-Nazi novel written under the Third Reich.

The 1938 version of Ernst Jünger's The Adventurous Heart: Figures and Capriccios must be considered a key text in the famous German writer's sprawling oeuvre. In this volume, which bears comparison to the Denkbilder of the Frankfurt School, Jünger assembles sixty-three short, often surrealistic prose pieces—accounts of dreams, nature observations, biographical vignettes, and critical reflections on culture and society—providing, as he puts it, "small models of another way of seeing things." Here Jünger experiments with a new method of observation and thinking, uniting lucid and precise observation with the unconstrained receptivity of dreams. He calls this method stereoscopy, a form of perception by which our commonplace understanding is extended to include a simultaneous awareness of additional dimensions of sense or value in the object observed. But equally important to Jünger is an intuitive receptivity that comprehends matters directly at the midpoint of the matter, making laborious determinations of the periphery superfluous—intuition is a master key that opens all, and not just the individual doors of a house. With these methods, Jünger attempts to penetrate to the hidden harmony of things that lies behind the dualities of surface and depth, image and essence. This superb translation offers Anglophone readers a fresh look at one of twentieth-century Germany's most extraordinary writers.

È il 1913. Ernst Jünger, diciottenne, fugge da scuola, acquista una rivoltella,attraversa in treno il confine con la Francia presentandosi a un ufficio direclutamento della legione straniera a Verdun. Poco tempo dopo eccolo inviaggio, con rissosi compagni, per Marsiglia; di qui l’imbarco per la costaafricana. Il giovanissimo Jünger passerà sei settimane nella legione,chiudendo la sua fuga quando un intervento del padre dalla Germaniaprovoerà il suo congedo.Un anno dopo si arruolerà di nuovo, ma nell’esercito tedesco, e andrà a combattere sul fronte occidentale la sua guerra, tra le «tempeste d’acciaio» che daranno il titolo a un libro memorabile. Fuggito da un’agiata esistenza di studente per poter vivere «arbitrariamente», Jünger farà la conoscenza, fra le mura di un fortino della legione, di quella speciale follia – seppur qui stemperata dal clima dell’avventura, dal colore dell’esotismo – che emana da un mondo chiuso di uomini in armi: un mondo insieme regolato e senza vera legge. Soprattutto, sperimenterà i limiti dell’avventura individuale, l’impossibilità di darsi un destino tutto personale; in realtà, egli è indotto a concludere, «nessuno può vivere arbitrariamente». Ma l’Africa è anche, per lui, il primo luogo in cui può scoprirsi osservatore – straordinariamente dotato – di una realtà al di là della vicenda attuale e contingente: il paesaggio, con il suo fascino immediato e la profondità del tempo che racchiude. E così, in questi Ludi africani, si rivela già in tua la sua mirabile forza percettiva il «contemplatore solitario».

Written in 1932, just before the fall of the Weimar Republic and on the eve of the Nazi accession to power, Ernst Jünger’s The Worker: Dominion and Form articulates a trenchant critique of bourgeois liberalism and seeks to identify the form characteristic of the modern age. Jünger’s analyses, written in critical dialogue with Marx, are inspired by a profound intuition of the movement of history and an insightful interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy. Martin Heidegger considered Jünger “the only genuine follower of Nietzsche,” singularly providing “an interpretation which took shape in the domain of that metaphysics which already determines our epoch, even against our knowledge; this metaphysics is Nietzsche's doctrine of the ‘will to power.’” In The Worker, Jünger examines some of the defining questions of that epoch: the nature of individuality, society, and the state; morality, justice, and law; and the relationships between freedom and power and between technology and nature. This work, appearing in its entirety in English translation for the first time, is an important contribution to debates on work, technology, and politics by one of the most controversial German intellectuals of the twentieth century. Not merely of historical interest, The Worker carries a vital message for contemporary debates about world economy, political stability, and equality in our own age, one marked by unsettling parallels to the 1930s.

D'Héliopolis, on pourrait dire que ce livre est le bréviaire de tous ceux que fascine depuis plus d'un demi-siècle l'oeuvre d'Ernst Jünger. Là sont contenus tous les grands thèmes de ses livres passés et à venir. Dans un univers où se mêlent intimement le romantisme le plus ésotérique et les techniques les plus fabuleuses de la science-fiction, l'auteur a campé une série de personnages « en situation » (le soldat chevalier; le sage détenteur des jardins secrets, le maître des pouvoirs magiques, le dominateur sans visage d'un univers de plus en plus déshumanisé, etc.), personnages et situations qui n'ont jamais cessé de hanter Ernst Jünger depuis les tranchées de 14 jusqu'aux chasses (plus) subtiles d'aujourd'hui. Héliopolis, un livre clé, un livre qui ouvre les couloirs mystérieux et sonores du labyrinthe de l'Existence et où, octogénaire, Jünger continue de cheminer de son pas tranquille de guetteur.

Libro usado en buenas condiciones, por su antiguedad podria contener señales normales de uso

Si ojeamos lo que hasta ahora se ha escrito sobre las drogas , sentencia Ernst Jünger , «encontraremos poca sabiduría y mucha ciencia ». Atraído desde siempre por ese mundo que sólo se alcanza en estados alterados, Jünger aborda en Acercamientos este tema desde un punto de vista multidisciplinar y, por supuesto, con mucha sabiduría . De hecho, propone un acercamiento vital al mundo de los paraísos artificiales : sueños, fragmentos autobiográficos, lecturas y experiencias alternan con encuentros con toda clase de personajes, sean célebres o anodinos. El libro no avanza por tanto en orden cronológico, sino al hilo de las asociaciones que Jünger establece entre la anécdota y las sutiles y sorprendentes reflexiones que ésta suscita en él. Estamos, pues, ante un cuaderno de bitácora sobre las experiencias del autor con sustancias que conducen a la ebriedad, ya sea alcohol , éter , cocaína , opio , hachís , LSD o peyote , pero también esas otras drogas llamadas soledad , música o juegos de azar . Mientras analiza ese estado en que la realidad queda suspendida, Jünger se pregunta también sobre las causas de la fascinación que los narcóticos han ejercido en la humanidad y sobre su influencia en las más diversas actividades, disciplinas artísticas y culturas, al tiempo que establece un riquísimo diálogo con los ilustres autores que lo precedieron en este viaje a la otra orilla: De Quincey , Poe , Baudelaire , Nietzsche , Aldous Huxley , Henri Michaux o Albert Hofmann .

poetic late novel, tr Joachim Neugroschel

Вперше перекладена українською мовою збірка «Вогонь і кров» присвячена фронтовим переживанням німецького письменника, філософа, ідеолога консервативної революції Ернста Юнґера під час його участі у Першій світовій війні. Натхненні та захопливі тексти звично для автора ведуться у формі щоденника, що, разом із листуванням з ріднею письменника, є логічним продовженням осмислення Юнґером феномену війни, побратимства та нового світового порядку з часу написання першого роману «В сталевих грозах». Книга призначена для всіх, хто палає серцем і на чиїх плечах лежить важкою ношею доля всього світу. Перекладач – Олександр Андрієвський.

Gerhard, a young man on the rise, is drawn into the seedy underside of Paris, where he witnesses the murder of a young ballerina

Su un'isola sperduta nel Mare del Nord un piccolo gruppo di persone, accomunate dall'aspirazione a conoscere il proprio vero Sé, si raccoglie intorno a un uomo misterioso. Signore della luce e nel contempo principe delle tenebre, costui conduce vita ritirata in una casa turrita, in compagnia di una domestica dalla risata beffarda, un pescatore con il petto sfregiato da una lama e una servetta silenziosa e ubiqua. Nei giorni in cui la notte è quasi inesistente o la luce dura un'ora, quando il tempo dell'orologio e della civiltà cessa di scorrere, i tre discepoli - un medico-filosofo, uno studioso di preistoria e una giovane donna - ascoltano gli oracoli del Maestro, e grazie ai suoi poteri ipnotici, o forse all'assunzione di allucinogeni, compiono ciascuno un viaggio nel proprio mondo intcriore. Viaggi a metà tra l'allucinazione e il delirio, l'evocazione e il sogno, attraverso un prisma di luci, suoni e colori in cui si intrecciano paesaggi tropicali e piane mitteleuropee, aurore boreali e interni contadini.

« Jardins et routes : ce titre paisible surprend, appliqué à un journal de la « drôle de guerre » et de la campagne de France de septembre 1939 à juillet 1940. C’est que l’auteur, glorieux soldat de la guerre précédente, a, selon sa devise, « mûri dans les tempêtes », et que ce quadragénaire s’intéresse, ni à la technique de la destruction ni à la recherche de la supériorité, mais à ce qui survit après toutes les batailles : le fleuve, les roseaux, les rigueurs intemporelles d’un hiver presque semblable aux autres ; le calme des vastes plaines françaises et la splendeur des jardins, à peine troublés par l’agitation et le passage des guerriers et des fugitifs ; les témoignages d’une très ancienne civilisation, qui a connu bien d’autres épreuves et en connaîtra encore. » (Henri Plard)

This book was originally written by Jünger as a 'blueprint' for a post-Nazi settlement if the German Army had succeeded in assassinating Hitler. This essay (it really is quite short), according to the author's foreword, was sketched in 1941 and completed in the summer of 1943. The reason Jünger mentions this is that it shows he was working on this essay before Germany began losing the war. However, this 'alibi', which I doubt, is not essential for him personally; his anti-Nazi novel "Auf den Marmorklippen" ("On Marble Cliffs") had been published in 1939. Also, keep in mind that Jünger, unlike Heidegger and Carl Schmitt, refused to join the Nazi party.

Forse Ernst Jünger ha stretto un patto segreto con il tempo. E forse questo patto è stato tanto efficace – in una vita che ha raggiunto la soglia dei cento anni, dopo aver attraversato tutte le bufere del secolo e aver assistito per due volte al passaggio della cometa di Halley – perché Jünger, anziché fuggire il tempo, lo ha sempre indagato con amorosa pazienza. Per catturare l'essere imprendibile per eccellenza egli ha avuto anche l'accortezza, con questo libro, di scegliere non già la via della pura speculazione ma quella della divagazione, alla maniera dei grandi eruditi seicenteschi. Così al centro ha posto un oggetto, l'orologio a polvere, che si offre a noi come un «geroglifico del tempo». E intorno a esso, con giri sempre più larghi, ha spinto la sua analisi a investire i diversi modi di vivere il tempo che hanno scandito il corso della civiltà. Dalla polvere che scorre insensibilmente all'interno di quell'oggetto pieno d'incanti che è la clessidra alla ruota dentata dell'orologio meccanico, dal tempo che viene lasciato essere al tempo che viene prodotto: attraverso la storia di questi oggetti, attraverso il succedersi di queste concezioni, una lunga vicenda ci conduce fino a oggi – e ci fa capire alcuni presupposti taciuti della nostra esistenza. Jünger ci guida in questi meandri con sapienza e delicatezza, senza precipitarsi alle conclusioni, ma anzi soffermandosi come un antico artigiano su una miriade di oggetti e di immagini – che costellano le pagine di un libro sicuramente fra i più felici e accattivanti della sua opera imponente. Il libro dell'orologio a polvere è apparso per la prima volta nel 1954.

Tres diarios componen este volumen, los titulados «Segundo diario de París» (1943-1944), «Hojas de Kirchhorst» (1944-1945) y «La choza en la viña (Años de ocupación)» (1945-1948), y en ellos Jünger narra, casi día a día, su experiencia de la Ocupación alemana, sobre todo en la ciudad de París, hasta que, de pronto, se precipitaron los hechos que condujeron a la caída de la capital francesa y a la liberación.Pocos pueden dar cuenta de este periodo tan contradictorio de la historia contemporánea como Jünger, particularmente esos años que, en realidad desde la primera guerra mundial, él llama «de la catástrofe». Con sus anotaciones de ese periodo, proseguimos la publicación de los diarios del pensador alemán en la colección Tiempo de Memoria.

Libro usado en buenas condiciones, por su antiguedad podria contener señales normales de uso

Das abenteuerliche Herz: Erste Fassung - Aufzeichnungen bei Tag und Nacht

by Ernst Jünger

Rating: 4.2 ⭐

Jüngers Prosavignetten in ihrer ersten Fassung – ein Wendepunkt seines literarischen Schaffens.Das Buch, erstmals 1929 erschienen, nimmt unter Jüngers Schriften eine Schlüsselstellung ein, auch gegenüber der späteren, stark veränderten Fassung »Das Abenteuerliche Herz. Figuren und Capriccios« (1938). Es stammt aus der Zeit, als die literarischen Aggressionen dieses Autors noch in engem Zusammenhang mit seiner nationalrevolutionären Publizistik geschahen. Jüngers Nähe und Differenz zu anderen literarischen Bestrebungen, vor allem denen des Surrealismus, werden nirgends so deutlich wie hier.Jünger war bereits als Autor der Kriegsbücher in Erscheinung getreten und bekannt geworden. Doch mit diesem Werk, das gleichwohl noch den zeitgeschichtlichen Bezug erkennen lässt, wandelt sich Jünger auch vom Kriegsschriftsteller zum Literaten.

Teo y Clamor son compañeros de juegos y estudios ; apenas tienen, no obstante, nada en común. El primero se impone al otro con la natural crueldad adolescente con la que los espíritus fuertes dominan a los más débiles. Clamor es un soñador, un alma contemplativa, temerosa y sensible ; Teo, en cambio, es un jugador que ve la realidad como un campo de fuerzas donde hay que apostar para ganar. Presa del miedo que le inspira el fuerte temperamento de éste, Clamor le sigue en sus correrías en un mundo que le es ajeno, y que tal vez acabe con él… Inevitablemente, el lector se preguntará si estos dos niños extraños no serán como el doble trazo del tirachinas , ese instrumento mitad arma mitad juego que inspira una inquietante peligrosidad.

Erste Einzelausgabe, im Jahr zuvor als Teil des von Jünger herausgegeben Sammelbandes "Krieg und Krieger" erstmals erschienen. Behandelt die vollständige Mobilisierung aller Lebensbereiche im modernen Industriestaat für den Krieg.

Il nodo di Gordio: dialogo su Oriente e Occidente nella storia del Mondo

by Ernst Jünger

Rating: 3.8 ⭐

L'incontro tra Europa e Asia, carico di antiche fatalità e fino ad oggi incombente nel teatro della storia, è il tema del dialogo a distanza che Ernst Jünger e Carl Schmitt intessono nelle pagine di questo libro. Jünger vede nell'incontro-scontro tra Oriente e Occidente la contrapposizione tra due atteggiamenti umani fondamentali: da un lato l'ermetismo, l'arcano, la magia, la sacralità del sapere e del potere; dall'altro lo spirito libero, la circolazione delle idee, un potere temperato dalla ragione e dal diritto. A questa visione polarizzata del divenire storico, Schmitt oppone una concezione dialettica centrata sulla contrapposizione storica dei rapporti tra l'Oriente, compatta massa di terraferma, e l'Occidente, emisfero coperto di oceani.

Ce volume contientAvant-propos de «Rayonnements» - Jardins et routes - Premier journal parisien - Notes du Caucase - Second journal parisien - Feuillets de Kirchhorst - La Cabane dans la vigne Tome II :1939. Mobilisé par un régime qu'il déteste, Jünger est à nouveau sous l'uniforme. Ce n'est plus le même homme, ni la même armée. L'expérience, elle aussi, sera différente. Après une campagne au cours de laquelle il n'est jamais en première ligne, et à part une mission dans le Caucase comme observateur, il est un occupant à Paris, puis le chroniqueur d'un coin d'Allemagne occupée. Les journaux de la Première Guerre s'organisaient en grands chapitres ; ceux de la Seconde sont datés au jour le jour. Dans un décousu apparent et très concerté, ils font place à des notations sur les opérations militaires, à des rencontres avec écrivains et intellectuels, à l'examen de soi, des hommes et de la nature, aux amours, aux rêves, aux lectures. Jünger lit notamment la Bible ; le christianisme devient pour lui un allié contre le nihilisme triomphant. Sans dissimuler son hostilité aux nazis et à l'antisémitisme officiel (il lui arrive de saluer militairement les porteurs de l'étoile jaune), il reste à son poste et n'attaque pas le régime de front. On parle d'émigration intérieure pour qualifier cette position complexe, que les contempteurs habituels de Jünger simplifient à l'envi. Hannah Arendt était plus nuancée. Tout en constatant les limites de cette attitude, elle voyait dans les journaux de l'occupant Jünger «le témoignage le plus probant et le plus honnête de l'extrême difficulté que rencontre un individu pour conserver son intégrité et ses critères de vérité et de moralité dans un monde où vérité et moralité n'ont plus aucune expression visible».

Nel 1950, in occasione del sessantesimo compleanno di Martin Heidegger, Ernst Jünger pubblicò il saggio Oltre la linea, dedicato al tema che attraversa come una crepa non solo tutta la sua opera, ma quella di Heidegger e tutto il nostro il nichilismo. Questa parola era stata evocata da Nietzsche, come se in essa si preannunciasse un «contromovimento», un al di là del nichilismo. Dopo che la storia ha «riempito di sostanza, di vita vissuta, di azioni e di dolori» le divinazioni di Nietzsche, Jünger si domanda in questo saggio, che rimane uno dei suoi testi essenziali, se è possibile «l’attraversamento della linea, il passaggio del punto zero» che è segnato dalla parola niente. E «Chi non ha sperimentato su di sé l’enorme potenza del niente e non ne ha subìto la tentazione conosce ben poco la nostra epoca». Cinque anni dopo, Heidegger raccolse la sfida e rispose a Jünger con un testo che è anch’esso essenziale nella sua La questione dell’essere.Qui pubblicati insieme per la prima volta, questi saggi si presentano, oggi non meno di allora, come un dialogo teso all’estremo, dove risuonano al tempo stesso l’opposizione e l’affinità, e insieme come una doppia risposta a quel fantasma che Nietzsche definì «il più inquietante fra tutti gli ospiti»: il nichilismo.